100 Poems

Old and New

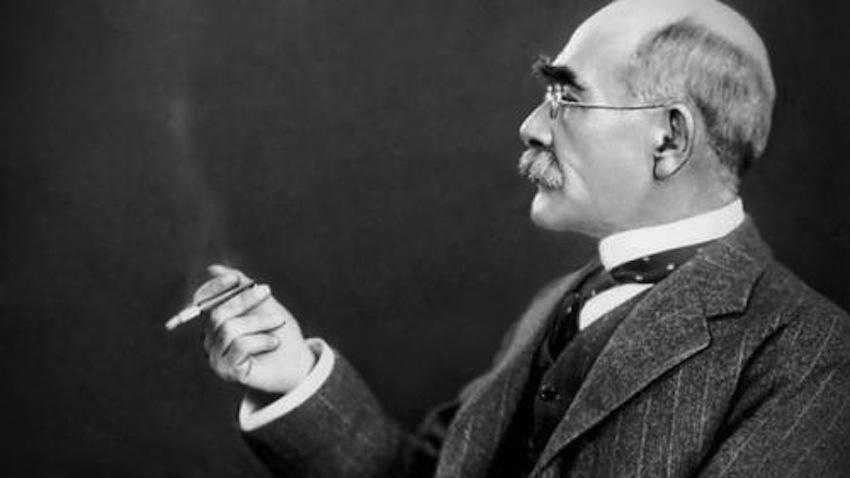

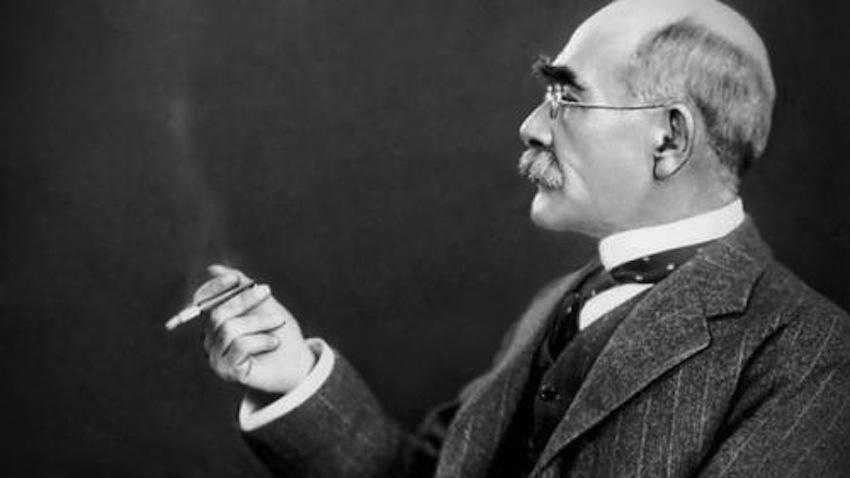

Rudyard Kipling

(Cambridge)

I'm thinking that one would have to be half-mad in this day and age to publish a collection of poems which include one entitled "White Man's Burden," another "The Wop of Asia," and a third given over in dedication to that ultimate Indian Uncle Tom ... Gunga Din. And yet Thomas Pinney, a (presumably) respectable Professor of English at Claremont's Pomona College has produced just such a book of Kipling's poetry. Although we note that he is now listed as "emeritus:" perhaps this volume explains why.And yet ... and yet, I suspect, all is not as it seems. If nothing else, "Gunga Din" has history on its side, and I recall, when I was a lad, my mother muttering to me, if I accomplished some special act with what she thought of as bravery or extra strength, "You're a better man that I am, Gunga Din!" And often, when we did reading --- she was an ever-faithful bed-time reader to her children, she would go through the entire poem, and together we would recite

Now in Injia's sunny clime,

Where I used to spend my time

A-servin' of 'Er Majesty the Queen,

Of all them blackfaced crew

The finest man I knew

Was our Regimental bhisti, Gunga Din!

'E was "Din! Din! Din!"§ § §

As far as "The Wop of Asia," this was a family code name that Kipling gave himself; his much beloved cousin Margaret Burne-Jones was "The Wop of Albion" or "The Wop of Europe."The poem is addressed to her. It appears in his Early Verse 1879 - 1889, was sent to her privately, and at the time, I think the word didn't have the code "Without Papers" which came later to be associated with Italians in America. ("Wop" also seems to have originated with the word "guappo" in Italian, related to the Spanish "guapo" --- pronounced wappo --- to be translated as "beautiful.")

The full poem:

The Wop of Asia --- that lordly Beast ---

Writes from His Lair in the burning East

To the Wop of Europe --- "Peace and Rest,

"From Allah who giveth them be in your Breast."Behold it was writ on our Brows at Birth

"We should sing in the East of the Sons of Earth:

(And how shall a Man, be He ne'er so wise

Escape that Sentence between his Eyes?)

Wherefore we sang and the Songs we send

May serve to amuse you in far North-End"Now the Gnat sings gaily at Eventide,

And the Bullfrog sings by the waterside,

"And the wind of the Desert across the Sands

"Singeth what no Man understands ---

"But whether we sing as These or worse,

Behold it is written here in our Verse."Thus a poem whose very title might make some in the 21st Century grit their teeth turns to something completely different when we know its roots as a witty, quite jocular letter of affection from the twenty-year-old young poet to his cousin. He writes in hopes that it "May serve to amuse you in the far North-End" for they are many of thousands of miles apart, he as "Gnat" or "Bullfrog," singing in a way that "no Man understands," even managing to include an astute aside that the older Kipling --- as well as his many fans --- would see as typical of his verse:

And how shall a Man, be he ne'er so wise

Escape that Sentence between his Eyes?Then there is "The White Man's Burden," composed by Kipling in 1899, sent to Teddy Roosevelt (while TR was still governor of New York, not yet president). It is an odd piece, for there are currents running through it that make it sound like the very opposite to what we would expect. It is often seen as a ukase for the United States on the eve of the Philippine-American War which started in 1899 (we took over what the Spanish had left undone. Like many wars it refused to end when it was supposed to --- it was "merely" the Tagalogs against the whites, yet it dragged on for another fourteen years, left a bitterness on the side of the Filipinos that continues to this day).If Kipling seems on the one hand to be egging us on, there are strange phrases that sound like a death-knell, the very opposite. We can send forth the "best ye breed" to "bind your sons to exile," to "wait in heavy harness" your "new-caught sullen peoples." It is an effort that will "seek another's profit,/ And work another's gain" as one of "the savage wars of peace," which will "fill full the mouth of Famine." Indeed, it was a war that saw "sloth and heathen Folly / Bring all your hope to nought."

The rest of the poem makes it no more appetizing, with all the ambivalences intact. This, the final verse but one, sounds even less exalting:

Take up the White man's burden ---

Ye dare not stoop to less ---

Nor call too loud on Freedom

To cloak your weariness;

By all ye cry or whisper,

By all ye leave or do,

The silent, sullen peoples

Shall weigh your Gods and you.§ § § Kipling was a fine story-teller, and I well remember drifting off to sleep to the adventures of Kim, or the fantasies of "The Just-So Stories." In his Barrack-Room Ballads he showed a kinship with the poor dogsbodies who ended up at the far reaches of the colonial empire and who --- it turned out --- paid heavily for their loyalty to 'Er Majesty the Queen (fatality rates among the common soldier in India or Africa were enormous, never mentioned to the new recruits.)

§ § § As I look over this collection, drawn by Pinney from his edition of the complete poems, there is much to cheer and little to despair. Kipling was a songster (as much as any performer in the Music Halls of his day) ... and an astute phrase-maker. We can mock his era, and the eon's mind-set, and yet come back again and again to recall the words that were drilled into us in such a loving way on the night-porch as we ourselves were starting to drift into the cool sleep along with the clear and gentle and wise voice sounding against all the sorrows and confusions that may have haunted us during the days that, at night, were made over again into a challenge, and a paean to a man of the earth, one of the "blackfaced crew ... the finest man I knew,"

'E carried me away

To where a dooli lay,

An'a bullet came an' drilled the beggar clean.

'E put me safe inside,

An' just before 'e died,

"I 'ope you liked your drink," sez Gunga Din.

So I'll meet 'im later on

At the place where 'e is gone ---

Where it's always double drills an' no canteen.

'E'll be squattin' on the coals

Givin' drink to poor damned souls,

An' I'll get a swig in Hell from Gunga Din!

Yes, Din! Din! Din!

You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!

Though I've belted you an' flayed you,

By the livin' Gawd that made you,

You're a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

--- L. W. Milam