TWELVE GREAT ARTICLESwe have put online almost four-hundred

articles on a variety of subjects:

love, hate, war, birth, death, art, music, etc., etc.

Here we have selected twelve for their

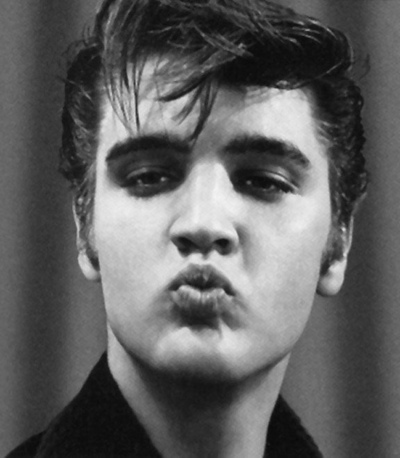

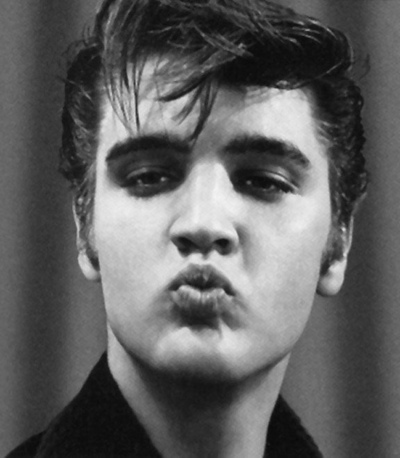

variety of thought, loving beauty, truth.Grandma Moses with

Pompadour and Peggers

Douglas Cruickshank

But the relative modesty of Graceland is what's so appealing about it. For all the attention it's engendered as a rock and roll icon (in Graceland: The Living Legacy of Elvis Presley, Chet Flippo calls it "The Plymouth Rock of Rock 'n' Roll", though I prefer to think of it as Presley's Monticello, his Giverny) what is immediately obvious when you enter is that it was actually someone's home, and that person was an even more extreme specimen than we suspected. Elvis, it turns out, may have made a good living as a rock 'n' roller, later sanitized into an "entertainer," but his first calling was folk artist. He was a primitive, a naive surrealist --- Grandma Moses with a pompadour and peggers --- whose most personally expressive work was his home, not his music. His talent went into his performances, but his genius was channeled directly into Graceland. Artists now hailed as brilliant post-modern recyclers of extravagant middlebrow aesthetics do little more than borrow shamelessly from a style Presley may not have invented but certainly embraced with enthusiasm long before the art elite's avant-garde irony squad got hold of it.Elvis, commingling the spirits of Louis XIV, Andre Breton and an assortment of Russian Futurists with his own, started ferociously imagining what Graceland's interior would look like even before moving in. He told a Memphis newspaper reporter he wanted "a black bedroom suite, trimmed in white leather, with a white rug." Chet Flippo reports that Presley also envisioned "the entrance hall painted to resemble the sky, with clouds on the ceiling and dozens of tiny lights for the stars." And that the singer planned for the living room, dining room and music room to have "purple wallcovering with gold trim [and] white corduroy drapes." (The Sun King-like notion of painting the entrance hall to resemble the sky not only prefigured the present treatment of the vaulted ceiling of the Forum Shops mall at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas by more than three decades, it anticipated a similar scheme applied to uncountable ceilings and walls of innumerable hippie pads long after Elvis took over Graceland.)

Unfortunately the purple and gold idea never came to be. A white, blue and gold motif were maintained in the living room and dining room during most of Elvis' years at the house. However, in 1974 Presley and his then girlfriend, Linda Thompson, tapped into some kind of divine Dadaesque inspiration when they gave the main rooms a crimson makeover complete with satin curtains and fake French Provincial furniture upholstered in red crushed velvet. It must have been thrilling to behold --- too bad the killjoys now running the place changed back to the blue and white decor.

Go to the full

articleDoing the Tarantella

At the Barnes FoundationViolette DeMazia was a study. She had a hawk-like face, sharp nose, thin-lipped mouth. Her eyes were hidden behind green tinted glasses. She dressed like a flamenco dancer, but only on the day that she did the Beethoven-Cézanne number did she dance like a flamenca.DeMazia was curator, chief instructor and watchdog at the Barnes Foundation, just outside Philadelphia. Albert Coombs Barnes had grown rich on Argyrol --- a noxious black substance that was, at the time, squirted in the eyes of all new-born babies to prevent pink-eye. In the early part of the century, he grew rich enough to collect fine art.

His taste was impeccable. At a time when people were mocking the Impressionists, he bought them up with a vengeance. In the 1950s, when I first came to the Barnes Foundation, there were, on hand, hundreds of originals, some 180 Renoirs, 70 Cézannes, 60 Matisses' --- and countless Van Goghs, Modiglianis, Soutines, Degas', Serauts, Manets, Monets, Picassos and Rousseaus. Plus a smattering of the older masters, the likes of Titian, Tintoretto, David, El Greco.

It was said that once, in 1924, after he had put together the major part of his collection, Barnes invited the Philadelphia press to the opening of his gallery just outside the city, in Marion. It is said that the press came, didn't stay long, went away, and wrote badly about his taste and his collection. Barnes, definitely a cranky eccentric, immediately closed the doors of the great white marble two-story complex, only allowing friends to view his astounding collection --- and the occasional drunk he picked up on the streets.

A short time later, however, he and his companion, Violette DeMazia, opened the door to specially picked students. They used the collection as bait to bring people to where they could teach people to see art the way they did. That is --- to ignore art history, ignore the artist's life, ignore criticism but, rather, to look at the paintings as if they were in a vacuum. Concentrate on the form, the color, the patterns, the style. To hell with Van Gogh's ear, Rosseau's boring weekday job, Gaugin's adventures in the South Seas, Seurat's suicide. The painting itself was the question, and the painting was the answer. It was not unlike "The New Criticism" they were teaching us in college: ignore the artist, concentrate on the art.

Go to the complete

articleThe Partial Vapor Pressure

of Khometz

Dr. PhageA Yiddish folktale recounts how an angel distributed human souls on earth from a stock he carried in two bags. In each region he scattered ordinary human souls from the larger of his two bags, with an admixture of just a few simple souls from the smaller bag. But the angel flew too low over one spot in Poland, and ripped the smaller bag on the highest branch of a tall tree. Before the angel could repair the bag, a cluster of simple souls all dropped into one place, which became the village of Chelm.Yiddish folklore omits mention of similar accidents on the American continent, but I know a place where one surely occurred. This place became the Jewish group home where my son Aaron, who has Down Syndrome, lives together with a half dozen other developmentally disabled young adults. I am a frequent visitor at Chelm West, often hanging around with the residents and occasionally joining them for dinner. Indeed, I can be found there often enough that sometimes, despite my age, I am taken for a resident myself. One such occasion occurred last Spring.

Aaron had invited me over on that particular evening because he was in charge of dinner, and he was creating his Spécialité de la Maison, grilled cheese sandwiches. However, just before dinner was to be laid on, we were visited by a local orthodox rabbi. Rabbi M., a Lubavitcher with beard, hat, and the mild, droning tones of Woody Allen playing a rabbi, comes by every now and then to provide the residents with helpful advice. So, dinner was held up while all of us simpletons sat around the dining room table listening to our visitor hold forth.

On this visit, the rebbe's topic was Passover, which was only a few weeks off. He began by reminding us how the Lord God led us out of Egypt with a strong hand, the historical event which Passover commemorates. However, Rabbi M. was by no means obsessed with history, and quickly moved on to matters closer to his heart, namely correct Jewish practice. His mild eyes began to gleam as he explained the rigorous measures needed to exclude any trace of khometz (leavened bread or pastry) from the home during Passover, replacing every last crumb by matzo.

Khometz during passover is even more toxic than treyf (non-kosher) food. The rebbe pointed out that we are permitted to consume as much as one part treyf in 30 parts kosher, because at precisely this fractional molar concentration, the treyf is diluted out the by the kosher. (I had often wondered about this myself, but had never worked out the physical chemistry in such detail.)

But khometz is even more potent than treyf --- in chemical thermodynamics, we would say that it has a higher activity coefficient --- and even one part in one hundred is too much. Much too much.

"Aha," I said to myself, "if we measured the partial vapor pressure of khometz, we could define proper kosher practice in terms of deviation from Raoult's Law."

Go to the full

articleHugh Gregory Gallagher

(October 18, 1932 - July 13, 2004)

L. W. MilamThey tell me that in his last hours he complained about being put in "the Japanese Wing" of the hospital. I know exactly what he meant. He and I often found ourselves being shuttled off somewhere we didn't expect to go, often in the wrong wing, on the wrong day, with the wrong set of operating instructions.The first time we met was in the spring of 1953 at Warm Springs Foundation in Georgia, in the ward that was to be our home for the next five months. They put Hugh in the bed across from mine, and he looked over and saw that I was doing the New York Times crossword puzzle. He didn't know that I could never get much beyond the second definition, that it was all show. Even so, he told me later: "When I saw you and the New York Times, I knew everything was going to be OK."

If we had to be somewhere with polio fifty years ago, Warm Springs was the right place. It was one of the most genteel rehabilitation centers on earth, a place of fun and life and impressive care. We had come from dingy little hospitals all over the country and suddenly we were in the palace of the gods --- with good and dedicated physical therapists and support staff, a graceful campus, wonderful food: a place which changed forever our feelings about ourselves, and our disease, and the man who had made this paradise possible.

We had fun there --- me and Hugh and Margot and John and Leumel and Gary. Hugh and Joe Mack once organized a testimonial dinner dedicated to fungus. They wrote songs, made long speeches about the skin condition that affected those of us who didn't have the power to reach down to dry between the toes. The theme was "There's a Fungus Among Us."

Speaking of themes, Hugh reported to us with glee that the official song of the National Infantile Paralysis Society was

When you walk through a storm

Hold your head up high

And don't be afraid of the dark...

Walk on, Walk on

With hope in your heart

And you'll never walk alone...He was also the first to note that when they brought comedies for the weekly showing at the Warm Springs movie house, we were laughing but no one could tell because most of us had lost our diaphragm muscles, the muscle that the able-bods use to laugh, sneeze or cough. The only way you could know that we thought Red Skelton was funny was not by the sound of laughter but by the shaking of our bony shoulders.

Go to the full

articleBetty

Michael Ingall, M. D."She'll never talk to you. She'll throw you right out."That's what the staff at the nursing home tells me about Betty, an 80-year old Greek woman who had a stroke years ago. Betty can say only "Tee-tee-tee-tee-tee." Staff are concerned that she seems to have given up on life. She refuses to eat. When her granddaughter from Maryland comes to visit, she gives her the cold shoulder. She scratched out the face on the photograph of her son, who is with the Army, stationed in the Far East. She has a new roommate whom she hates, because she can't boss her around the way she did her old one, who was more severely impaired.

Something tells me that extraordinary measures are necessary to reach this woman. And so, I take the hand of Cheryl, a warm and caring LPN, hold it high overhead, and lead the way into the room doing a Greek folk dance, the Yerakine, singing aloud in Greek:

Kinise...yerakine....ya nero...

It is one of those defining moments that make nursing home consultation such a joy sometimes. Betty looks up in astonishment and beams, screaming with delight: "Tee-tee-tee-tee-tee-tee!!!" She pulls us to her, hugging us with affection. She grabs a picture of her husband, pointing to him with animation. "Tee-tee-tee-tee," which means that she used to dance the yerakine with him. I ask her about her son, and she frowns, making a dismissive motion with her hand. I begin to name Greek foods --- moussaka, spanikopita, ouzo, Retsina wine --- and she beams again with delight. When I ask her if she would like to have Greek food here, she frowns and makes her dismissive motion. Cheryl and I take our leave, dancing and singing, and she waves goodbye, "Tee-tee-tee-tee-tee!!"

My recommendations to staff:

- Although she is thin, she does not seem emaciated to me and she has lots of energy. I wouldn't worry so much about her eating, although I would bring her Greek food, especially baklava, which is very fattening, and moussaka, which is nutritious and fattening.

- She is not clinically depressed, and I don't think she would benefit from antidepressant medication.

- Learn a little Greek to engage with her:

Hello (in the morning) = Kali merra

Hello (in the afternoon and evening) = Kali sperra

Good night = Kali nikkta

Thank you = Effkharisto

- Learn Greek dancing. Even if you don't reach Betty with it all the time, you'll feel better when you do it.

Bob Marley and

The 3AM Blues

Carlos AmanteaI open the door to look out at the world before I say adieu. It's dark, very dark. They've turned off the moon. Most of the stars are fading fast. There is a bird nearby, in the arroyo, singing, "It's real, it's real, it's real." Funny, I never heard that one before.I turn over on my other side where, because of my tinnitus, I can't hear my heart. The bird grows quiet, or maybe it just up and dies in sympathy. A Very Stupid Song starts up in my inner juke-box --- the one where you don't have to put in any coins, the one where they play the same song over and over again, about fifteen million times, till you get to know it perfectly:

Please don't worry

'Bout a thing

'Cause every little thing's

Gonna be all right...My Hit of the Week. Bob Marley. He's not worried. And, being charitable, he doesn't want me to worry, either.

I am not very interested in Bob Marley. If the truth be known, I can't stand Bob Marley. I would prefer anything other than Bob Marley. Give me Smashmouth, The Cramps, The Pet Shop Boys, The Goo-Goo Dolls. Give me Leprosy, Dengue Fever, The Blind Staggers. But spare me Bob Marley.

He wants me not to worry, but I do worry. I worry about global overheating, or whatever it's called. I worry about the Lakers, whoever they are. I worry about the sudden drop in the Dow. I worry about Monica Lewinsky's tummy.

I also worry about my workers, and their goddamn boombox, which started all this. Juan and Chiro and Leopoldo play that Bob Marley song ad nauseum. They think that Bob Marley is the bee's knees.

Tomorrow I will ask Chiro, ¿Cuántas veces hay que oir esa pinche canción? (How many more times am I going to have to listen to this miserable jerk?) I've asked him this before, several times, so I am pretty sure he will say, "¿Quieres que lo quito?" You want me to shut it off. He's very amiable. He also knows where the next paycheck is coming from.

He will turn it off. But we've gone through this particular song-and-dance before. I know that an hour later I'll be hearing some advice. From one B. Marley, off in the distance. He'll be telling me I don't have to worry 'bout a thing cause he knows, he just knows that every little thing's gonna be all right.

Go to the full

articleI'm Dying

Elizabeth Gips I'm dying of tobacco. My addiction, with its awesome needs, clutched me for years and years --- maybe a half century. I say its need, because I've learned at first-hand that the nicotine molecule creates an unusual appetite in some people; it not only latches on to the nicotine receptor sites in the brain...it creates more nicotine receptor sites. So the more you smoke, the more you have to smoke. And the more you smoke, the more the cilia in your lungs are damaged. Unable to clear the toxins, the cilia in the lungs begin to atrophy.

I'm dying of tobacco. My addiction, with its awesome needs, clutched me for years and years --- maybe a half century. I say its need, because I've learned at first-hand that the nicotine molecule creates an unusual appetite in some people; it not only latches on to the nicotine receptor sites in the brain...it creates more nicotine receptor sites. So the more you smoke, the more you have to smoke. And the more you smoke, the more the cilia in your lungs are damaged. Unable to clear the toxins, the cilia in the lungs begin to atrophy.I say, often and loudly, and most often around tobacco smokers,

If anyone who still smokes could live in my body for two minutes, they would never smoke again.

When I was a ten-year-old kid, dying with double pneumonia, it felt as though a heavy heavy stone was being pushed down on my chest. Up, up, one, two, three. Roll down. A true Sisyphus, using my little body to work out his human sentence, my body with the weight of the world killing me.

I didn't die, but I remember that time well. Sometimes now when I'm struggling to breathe, my chest won't expand. No oxygen. The stone again.

Or maybe it's like being inside an iron maiden, from the bottom of the rib cage to the shoulders. Poor shoulders. They're called into emergency action to act as muscles for the lungs. They weren't designed for that, so they get to ache from the tension.

Go to the full

articleThe Rooster in

The Wristwatch

Dr. PhageOne of my wristwatches has an alarm which mimics the sound of a rooster crowing. At some point in the distant past the alarm was set, God only knows how, to go off in the mid-morning, and I have no idea how to change or cancel its now irrevocable setting. Until recently I wore this watch every day. When the rooster sound went off in class or in a meeting each morning, I played innocent, looking around the room as if to discover where the sound was coming from. Eventually, this ruse began to fail, and to avoid further embarrassment I gave up wearing the watch.In one attempt to kill the alarm, I put it in my freezer for a week, but that didn't faze it. Not knowing how to unprogram the thing, I feared to throw it away, out of superstitious dread of what the garbage-men would think when they heard a rooster crow from inside my dumpster. I finally nailed the watch to the wall in my study, where it remains, sturdily crowing every morning at what it thinks is 9:41 AM.

In fact, I am getting just a little spooked by all the electronic devices that surround my life. This morning, a voice at my ear awakened me with the words: "If you want to keep hearing the insights and reflections of Scott Simon, just call up and pledge..." at which point I cut off the voice by throwing its host-device across the room. Then, I heated my coffee and doughnuts in the microwave, which fused the doughnuts and their plastic wrapping into a tasty amalgam, and went down to my study in the basement level to listen to the rooster crow.

Passing through the central room of the basement, I paused to turn off the TV, which turns itself on early every morning. My retarded son Aaron, a frequent visitor, long ago programmed the thing to do that, and I haven't the faintest idea how to un-program it. In my study, I picked up the ringing telephone, only to hear a monologue by a dead voice which claimed to be the mother of a candidate running for the senate. Normally, I interact with these robot voices only when I call any office for information, but now they are calling me, for God's sake, and they are somebody's mother.

Go to the full

articleBeautiful Summer in

New Jersey

B. W. McClellanThe family boarded the towering hulk called the Normandie, and my sister and I were boarded out for the summer somewhere in New Jersey, with the Andersons.I wish I could remember what they looked like, the Andersons. You would too, after you hear what I am going to tell you. But, bless me, all I can remember about Mr. Anderson is the rimless glasses, much like the ones I'm wearing. As for Mrs. Anderson, it was the false teeth. And me, in the bathroom, fascinated, mesmerized by the uppers in a jelly-glass of water, on the shelf.

One day in a bright-hot, sun-washed summer in New Jersey, the lunch bell was rung for the fifteen summer-orphans. Only Robbie, black-haired and having too much fun, didn't hear it, didn't come. He wanted to hang, feet just missing the ground, another minute or so on the Jungle Gym.

So Mr. Anderson went out to where Robbie was hanging by his hands another minute on the Jungle Gym and told him something and Robbie continued to hang by his hands from the Jungle Gym for the whole lunch period with tears streaming from his large brown eyes. Robbie paid singular attention to the lunch-bell after that.

One morning, in that bright-washed summer in New Jersey, Ralph (taller than most) complained about the toast at breakfast. Claimed that Mrs. Anderson had burned the toast. Claimed that he didn't like burned toast. Every morning thereafter, Ralph ate breakfast standing up behind the pantry door, ate his breakfast of unbuttered burned toast. We heard no more complaints about burned toast from Ralph.

One noon, in that bright sun-rinsed sky-beautiful New Jersey summer, Mary climbed the stairs to the attic to study her math with Mrs. Anderson. In fact, Mary, a very bad student in math, climbed the stairs every noon to study math in the attic with Mrs. Anderson. And every day, we heard the impact of Mrs. Anderson's teaching, in the form of an old, hard, red slipper. "Ow, ow, ow," Mary would cry, resisting her math. And every afternoon, in that bright summer, Mary would come back from her hard math lesson, and we would gather around her to tell her how she sounded, as the words were being pounded in. "Ow, ow, ow," that's what we heard, we would tell her. She didn't say very much, didn't seem to hear us very much.

Go to the full

articleThe Rejection Slip BluesMy friend Margot knew Philip K. Dick, the sci-fi writer, author of "The Minority Report," "Blade Runner," "Total Recall." She tells me that in a corner of the room above his desk he had glued the many rejection slips he had gotten over the years. She said they covered the better part of two entire walls. He had them right there where he worked, so that he could look up at them, know the chances, remain humble.After sending off 362 copies of my package, and after two months, I have gotten back, so far, 207 written or printed rejections, 21 e-mail rejections, a few kind regrets, and a very few invitations to send the entire manuscript.

The rejection slips fall into four general classes: the scrawl, the cold no, the warm no --- and the (yay!) "please send more."

The Scrawl is always slashed across the top right-hand corner of the original letter of inquiry. It's usually "No," or "Sorry," or "No thank you," or "Not for us." The Vines Agency uses a 4-point rubber stamp advising me that my manuscript did not meet their needs at this time. Another scrawl snarled, "Not for me & yr mass mailing, FYI, is not an asset." The signature was illegible, so I had no way of responding with a Hate Missive.

Printed letters of rejection range from a brief cold "No" to the two-page warm, friendly, I-would-

if-I-could- but-I-simply- can't. The prize for the most picayune of the former goes to Marcia Amsterdam, with a note the size of a calling card, telling me that Geezer "doesn't meet our present needs." Ruth Nathan comes in second with a hand-written, Xeroxed quarter-page "So sorry --- no new clients at this time." Harold Matson gets a third for the same message but first prize for the concluding adverbial twist: "Thanks for thinking of us, nevertheless." Robert Madsen's response, 1 in. by 6 in., also had syntactical difficulties:

We've reviewed your submission, however, regrettably, it's not deemed appropriate that this agency represent it.

Angela Rinaldi's rejection slip was bordered in funereal black and was the most artful. Peter Rubie wanted to be sure that I would not "take this rejection as a comment on your writing ability because it is not intended to be one;" then he went on to suggest that my writing induced a certain lassitude:

Alas, I can only properly represent material that excites me or interests me, and unfortunately your material didn't do that.

Trafalgar Books told me they only handled equestrian writing, and Jeanne Fredricks said that she was "not taking fiction." Thanks, Jeanne. Cherry Weiner opined that she had a "very full list" but invited me to meet her at a conference even though she stated, in proper cautionary fashion, "Listening to me lecture is not enough." She attached some syntactical convolutions of her own:

I really need to have time on a one-on-one with you to have actually asked for your manuscript.

Go to the full

articleGod vs. Gawd

A. W. AllworthyThere seem to be two gods floating around nowadays. One is called god; the second, Gawd.God is the one that many of us grew up with. Many years ago he finished his work making this universe and since then has gone off to start several billion other universes by doing something called The Big Bang.

Although many of us address him in love or in desperation, he rarely replies. Not to be bothered. If you were off building another cosmos, you'd probably do the same.

Those who want to question god might as well forget it. One sage asked "If god is all wise, all seeing, and all compassionate, why is there so much pain, misery, suffering, and agony in the world?" The answer: to thicken the broth.

Despite this fecklessness, many of us are rather fond of our divine. We are given the freedom to live more or less the way we wish, knowing that if we don't go around killing or hurting others (or ourselves), god will probably leave us alone --- or at least won't be bothering us with questions about our nighttime habits.

We, in exchange, promise not to bother him (or her or it) with silly paradoxes or needs: "What's the meaning of life?" "Why, indeed, are we here?" "Could you please fix my backache (or my bank account)?"There is another divine whose name is Gawd. He works for Pat Robertson, Ralph Reed, Jerry Falwell, James Dobson, and other folk who are called Evangelicals. They have a direct line to His office because they are forever and a day reporting back to us what He thinks about us which is mostly bad.

Go to the full

articleÁngelThe Mass for Ángel was very noisy. Next to the choir, there was a ten-piece brass band complete with snare drum and bass. The choir would sing for a bit, then the band would come in, then the choir would sing some more, then the brasses would let loose with a blast of mourning --- loud, discordant, wonderfully off-key. The tiny cathedral of Santa Clarita could barely contain the sound.Near where I was sitting, there was the coffin with thick panes of beveled glass on the top and sides. I was thinking how much money they had spent to bury my poor Ángel, wrapping his body in fine white muslin. But at the end of the service, when we set out for the graveyard, I realized that the glassed-in box was that of another angel, from other centuries, long, long ago. Not my recently departed Ángel.One of the reasons I took Ángel on as a worker was because the neighbors told me he was sober and hard-working. Still, you and I have hired Personal Care Attendants who seem perfectly nice and responsible and then after a while you find they are AWOL for a week because of demon rum or being gooned out on some drug. From what I heard, though, Ángel was a respectable family man. They assured me that he would keep his partying down to respectable levels.They were right. Mostly. Ángel wasn't interested in drugs, and didn't drink more than a couple of times a year. But when he did tie one on, it was a doozer.

And it was one of those rare times that ended his life, at age twenty-nine, at 8:03 of an evening, on the road between Santa Clarita and La Misión: a head-on with a semi.

§ § § I started driving the three thousand miles down to Santa Clarita in the fall, a dozen years ago. These six-month visits were a Christmas present to my joints. As we age, as you know, the cold weather begins to speak loudly to and through our bones.

Ángel worked in the orchard next door to my pied-à-terre. One day he was cutting out a path with his machete and I asked him if he knew anyone who could help me. All the things I had done so easily before now seemed to be slipping out of my grasp.

Getting up in the morning, bathing, getting into the car, getting out of the car --- none of these were easy any more. I had been so independent, fiercely so, for such a long time ... and now I was losing it.

Ángel signed on to work for me six days a week, and soon enough, when things deteriorated further, he brought in cousin Chuy for the times when he had to be with his family.

Whatever I paid the two of them was miserable by the standards to the north. Yet they were the perfect PCAs, the ones you and I have been seeking for so long. They were masters at getting me from bath to chair, from chair to car, from car back to chair and from thence to bed. I trained them to be resourceful, and the way they dressed me and got me about could best be described as elegant.

Most of all, Ángel knew how to get me in and out of the wheelchair in a single, exotic turn ... never stepping on my toes, never banging my knees. His moves were a fusion of the two of us, a dance: his body as an extension of my own. He knew what I needed well before I did.

Ángel was married to lovely María. He was a good father and husband. And, after I had gotten to know him over the years, he became a man of my soul as well.

§ § § Philip Roth once wrote, "You know, passion doesn't change with age, but you change. The thirst ... becomes more poignant."

I have something quite, well, odd to confess here, but I don't want you blabbing it all over town, OK? I had this thing for Ángel, had it for several years.

His eyes were tranquil, and as black as sin. His back was straight and dark, the color of cedar, or --- perhaps --- heart-of-pine. It was the back that you and I might have had so many years ago had things worked out differently.

During the day, Ángel went about the compound like a panther, appearing and disappearing between the mango trees and the palms and the fruit trees. As he moved, I swear to you, he floated an inch or so above the ground, the sun showering gold coins on his golden back.

I never told him about this thing I had for him. I didn't want to queer my luck, in a manner of speaking. And I certainly didn't want to lose him. But he was wise; he knew.

It is a little strange, isn't it? In fact, I can't think of anything more dotty than a 75-year-old geezer making goo-goo eyes at a man of twenty-nine with wife and child. Can you? It's not all that queer, though. Chaucer wrote about it, as did Shakespeare and Ovid. It was called "April and December." December was the one with the white hair and the shakes.

I figure it was Ángel's fault. Except for the times when we went to town to go to the public market or the doctor, he refused to wear much in the way of clothing, the bastard.

The average mean temperature in Santa Clarita hovers around ninety during the day. Under such conditions, Ángel didn't much cotton to shirts or shoes, and his shorts rode dangerously low on his narrow hips, causing some discomfort to a nearby codger who had been warned more than once about his blood pressure.

At bedtime, Ángel gives me my last margarita of the day, then takes me into the bedroom. He checks to make sure that I have enough water and soda. I always take care of the Jumex bottle myself. I don't want him to know that I have to piss in a glass bottle, three or four times a night. I clean it during the day when he's out watering the garden.

He puts his arms around me, helps me from chair to bed. He tucks in my legs in and draws up the sheets. He leans over me to put the glaucoma medicine in my eyes. His face is a few inches from my own. The gentle mouth, the arched nostrils, the astonishing eye-lashes. The eyes, as I say, as black as sin.

He sets up the pills for me to take: one for the arthritis, one for the diabetes, one-and-a-half for the blood pressure, one-half for the sleep, and the smallest for the night terrors.

I can smell the night-blooming jasmine that he has planted, so profusely, just outside my window. He turns out the light and I can see him now, standing straight, a shadow in the doorway. (Alas, he sleeps outside, in the patio, in a hammock, wrapped in a sheet, like a mummy. The sheet protects him from the mosquitoes.)

"¿No hace falta, Don Carlos?" Do you need anything else, Don Carlos?

"No," I say: "No, ya tengo todo lo que necesito." I have everything I need. "Gracias por todo, Ángel." Thanks for everything, Ángel. Thanks for caring for me. Thanks for being here. Thank you, thank you.

§ § § Chuy rounds up three young men help him get me to the cemetery from the cathedral, up-hill and down-dale. The four of them are to float me and my wheelchair to a shady spot a few yards from the grave, under the wisteria.

Unfortunately, one of the newly drafted is blind drunk and they damn near dump me atop Sra. Gloria Luz (1931 - 2006): born the same year as I; retired from life shortly before me.

The cemetery at Santa Clarita is all sixes and sevens. No groundskeeper here. The summer storms have eroded the earth from around the graves. The tombs are simple, as befits a simple village.

Chuy wants to part the crowd to get me up next to the grave but I hold back. I'm not too keen on having the villagers see this old doofus make such a spectacle of himself, in front of everyone, eyes leaking so much woe ... for all to see.

§ § § Just before the Mass, Chuy told me about something rather strange that morning. It had happened to him when he dropped by the house where María and the neighbors had prepared the body for viewing. There were thirty or forty lighted candles, a huge flowered cross, and a black and white photograph of Ángel from years ago. He was wearing his hair straight and long under a black caballero's hat, the one with the wide brim.

He is lounged back, looking directly at the camera. It was a shot taken before he had met and married María, before I had come to know him, long before his son Carlos, my godson, had appeared on the scene.

Chuy studied the photograph for awhile. Then he turned to pay homage to the lone figure in the coffin. "At once," he told me later, "I had this strange prickly feeling that Ángel wasn't dead at all. It felt like not only was I watching him, but he was watching me."

"Then, just like that, all of a sudden, he moved," Chuy said. "Not all of him. Just his eye, his right eye. 'This is crazy,' I thought. 'The son-of-a-bitch isn't dead at all.' I swear to you, Don Carlos, Ángel winked at me."

Dear Ángel. At such a solemn moment. Giving us a little wink. To let us know, in case we weren't sure, that everything was just as it should be.