Russian Children's Literature 1920 - 1935:

Beautiful Books, Terrible Times

Julian Rothenstein,

Olga Budashevskaya,

Editors

(Redstone Press

7a St. Lawrence Terrace

London W10 5SU)

What could be more cheerful than a collection of more than 300 illustrations from Russian children's books 1920 - 1935? Funny-looking cars and buses and trams, funny-looking furry animals, funny-looking people. Multicolored huge butterflies, trees like giants, furry kangaroos, frogs that write, giraffes on parade. Poems, all in Cyrillic of course, but some nicely translated,And after awhile

A crocodile rang from the Nile:

"I will be ever so jolly

If you would send us a pile

of rubber galoshes ---

The kind that one washes ---

For me and my wife and for Molly!"Then there are bears and fish and dancing boys and girls and a streetcar called ТРАМВАЯ ... and a couple of birds dressed like Russian bears,

Two owlets, two brothers,

Took hold of a seat.

They don't mix with others,

They sleep or they eat.(There's a kangaroo also dressed like a Russian bear:

Little long-tailed Kangaroo

It's a merry book, yet in the Introduction, Arkady Ippolitov reminds us that in Russia, during the time of the publication of these volumes, there were between 4,500,000 and 7,000,000 bezprizorniki --- children "who had never known either family or home,"

Has a baby sister too,

But the mother's keeping her

In a belly-bag of fur.)A specifically Russian problem of "neglected children" --- the result of the mass executions, artificially induced hunger, arrests and forced relocations carried out in the name of the future.

"Given that Russia's dwindling population in those years numbered somewhere around 120,000,000 people, this means that almost every third child in the country was homeless."

§ § § In the Foreward by Philip Pullman, we are told that the artistic style of these books was known as Constructivism: "Basic geometrical shapes, the square, the circle, the rectangle, are everywhere, flat primary colours dominate." But there are many variations on a theme here, and he even discovers one of Cézanne's fruit-bowls turning up "most unexpectedly" in Nikoai Troshin's Colouring Book.

Inside the Rainbow does have an undertone of melancholy. It may be because of several dour poems chosen by the editors, such as Daniil Kharms' "A Man Walked Out Of His House,"

Then once upon a morning

he entered a dark wood

and on that day

and on that day

he disappeared for good.If anywhere at all you meet

with him by any chance

then run and tell,

then run and tell,

then run and tell us, please.Or perhaps it is the inclusion of Osip Mandelstam's 1908 poem,

To read only children's books, treasure

Only childish thoughts, throw

Grown-up things away

And rise from deep sorrows.I'm tired to death of life,

I accept nothing it can give me,

But I love my poor earth

Because it's the only one I've seen.In a far-off garden I swung

On a simple wooden swing,

And I remember dark tall firs

In a hazy fever.As the Revolution wore on, it became harder for writers and illustrators of children's books, especially in the time of Moscow Trials. There is, for instance, this critique of the great children's book writer Kornei Chukovsky, published by one Vygotsky in Educational Psychology:

It is not hard to instill the taste for such dull literature in children, though there an be little doubt that it has a negative impact on the educational process, particularly in those immoderately large doses to which children are now subjected. All thought of style is thrown out, and in his babbling verse Chukovsky piles up nonsense on top of gibberish. Such literature only fosters silliness and foolishness in children.

This dourness also turns up in quotes from Lenin's speeches and writings to be found here and there throughout Inside the Rainbow. This is part of a speech given before the Young Communist League in October of 1920: "Our school must train the young to be participants in the struggle for emancipation from the exploiters. The YCL will justify its name as the league of the young communist generation only when it links up every step of its teaching, training and education with participation in the general struggle of all the toilers against the exploiters ... it must know that the whole purpose of life is to build this society."

And here we find a few of the "Notes on Child Care" posted in the Museums of Mother and Child in 1932:

- Never take a child to motion pictures or the theatre.

- Do not help a child who is in a difficult situation unless it be dangerous, he must learn to care for himself.

- Do not tell stories to child before he goes to sleep, for you will disturb him with new impressions.

- Never tell a child about things he cannot see. (This means that fairy stories should not be told to children.)

Yet some of the writings here come with the touch of the ecological, a wisp of humor. This is from Ivan Bunin's diary, Cursed Days.First it was the Mensheviks and their trucks, then the Bolsheviks and their armored cars. The truck: what a terrible symbol it has become for us! How many trucks have been part of our most burdensome and terrible memories! From the very first day, the Revolution has been tied to this roaring and stinking animal, filled to overflowing first with hysterical people and vulgar mobs of military deserters, and then with elitist-type convicts. All the vulgarity of contemporary culture and its "social pathos" are embodied in the truck.

There are even a few cheerful passages, such as Viktor Borisvich Shklovsky's memoirs of the February revolution, a child's playground of cars and trucks banging together:

And throughout the city rushed the muses and furies of the February revolution --- trucks and automobiles piled high and spilling over with soldiers, not knowing where they were going or where they would get gasoline, giving the impression of sounding the tocsin through the whole city. They rushed around, circling and buzzing like bees.

It was the slaughter of the innocent cars. The countless automobile schools, in order to fill the motorized companies, had been cranking out hordes of drivers with half an hour's training. And now these half-trained characters gleefully fell upon the vehicles.

The city resounded with crashes. I don't know how many collisions I saw during those days. Later on, the city was jammed with automobiles simply left by the wayside.

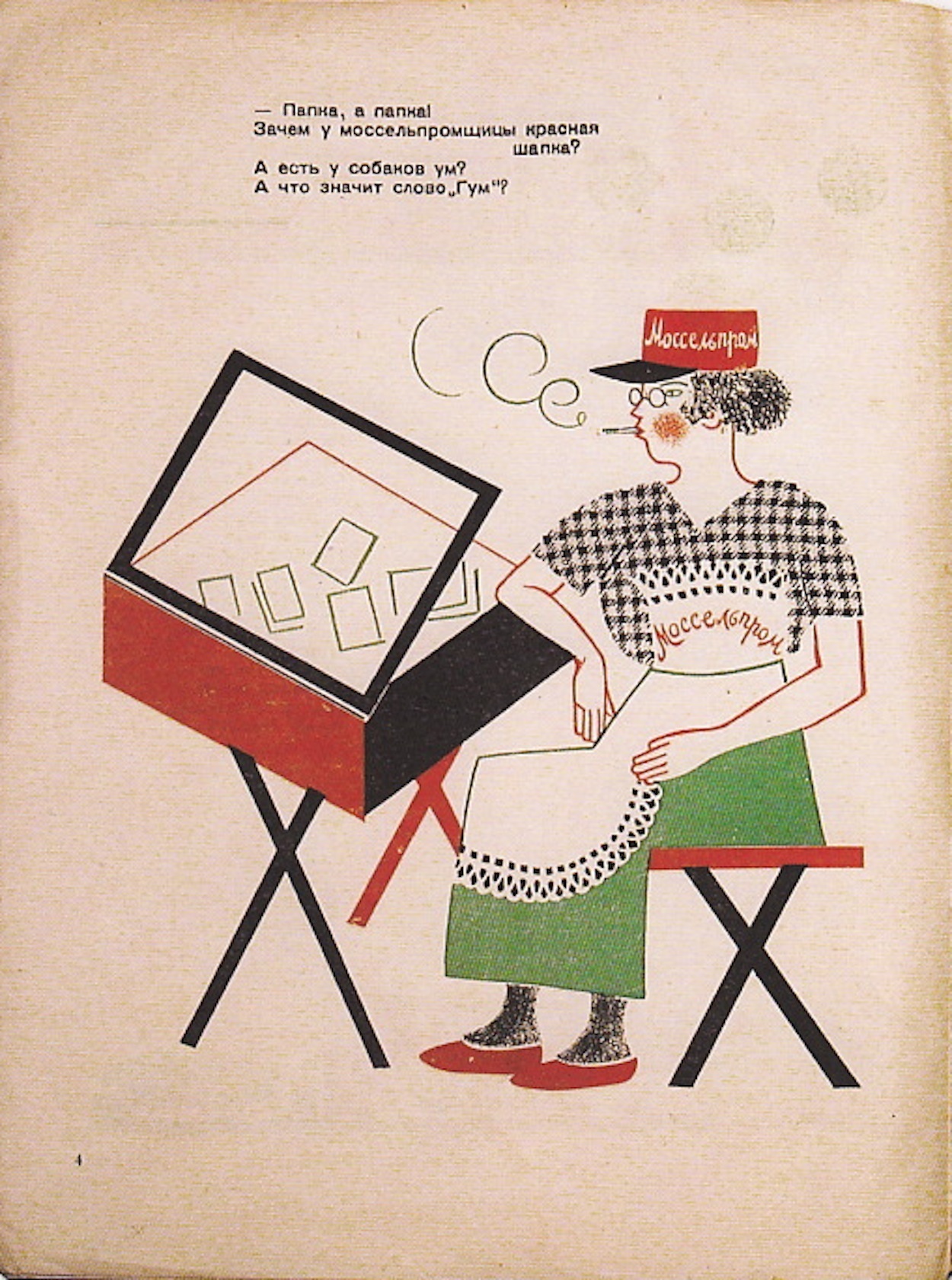

Perhaps it is best to leave the solemn prose to the solemn revolutionaries, and, by contrast give our best attention to the hundreds of glorious pictures reproduced here --- geese ducks chickens cows blackbirds ... horse-and-carriage, merry-go-rounds, even angels and rainbows, and a droll picture of a lady selling cigarettes, with the following inscription:--- ПаДпжа, а ДаДпжа!

Зачем у уосселъДромщицьi красная шапка?

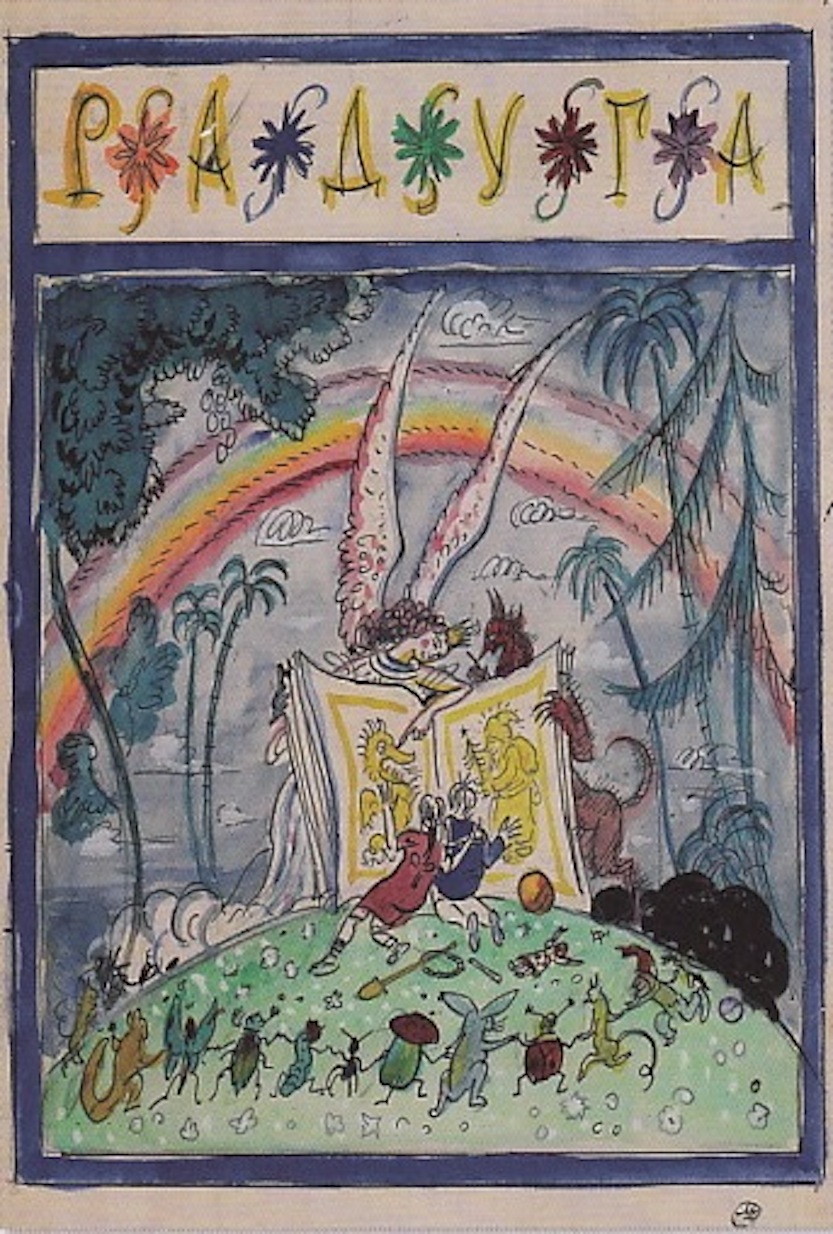

Best of all, we leave you with this picture, one that gave us the title of this gorgeous volume, a book from and for the young, one that is clearly a labor of love: РАДУГА.