All Men Are Brothers

Mohandas K. Gandhi

(Bloomsbury)

All Men Are Brothers was first published in 1958 bY UNESCO and Columbia University Press. It consists of hundreds of excerpts from the writings of Mohandas Gandhi --- collected into twelve chapters. It embeds the dictates on which he built his life, in his own words: non-violence, vegetarianism, non-attachment, reverence for life, celibacy, anti-colonialism, and, finally, the struggle against the concept of "untouchables."By collecting so many passages from his books, articles, newspaper writings, and speeches, All Men Are Brothers becomes a compendium of the Best of Gandhi. And since he was no slouch as a writer, many of his comments turn into jewel-like points of understanding. This from 1939, on nonviolence:

Nonviolence and cowardice go ill together. I can imagine a fully armed man to be at heart a coward. Possession of arms implies an element of fear, if not cowardice. But true nonviolence is an impossibility without the possession of unadulterated fearlessness.

Notice the elegant phrasing: nonviolence and cowardice "go ill" together; possession of arms "implies an element" of fear; true nonviolence demands "unadulterated fearlessness."

In this and many other ways, Gandhi never ceases to surprise the reader. Once he went to a barber in Pretoria, where he lived at the time. The barber "contemptuously refused to cut my hair. I certainly felt hurt, but immediately purchased a pair of clippers and cut my hair before the mirror."

I succeeded more or less in cutting the front hair, but I spoiled the back. The friends in the court [he was a lawyer in South Africa at the time] shook with laughter.

"What's wrong with your hair, Gandhi? Rats been at it?"

"No. The white barber would not condescend to touch my black hair," said I, "so I preferred to cut it myself, no matter how badly."

He tells us that his reply did not surprise his friends. But the next thought may surprise the reader:

The barber was not at fault in having refused to cut my hair. There was every chance of his losing his custom, if he should serve black men.

Gandhi gently puts himself in the barber's seat (as it were) by saying, "I understand where he's coming from."

If he were to cut the hair of an Indian, he would lose his business. Better for me to learn to do it myself.

There is a mixture of gentleness and pride in these words. Instead of condemning a man for being a bigot, he's saying, let's choose a better way out of this muddle; for all of us: the barber, me, you.

§ § § At times, there are some awkward surprises in Gandhi's writings, especially for those who come close to believing him to be a saint. He is militant on the subject of chastity, offering thoughts that might offend many. For example, he has an unalterable vision of himsā (violence) against ahimsā (nonviolence). Especially when the question of sexual purity is at stake:

Suppose, for instance, that I find my daughter, whose wish at the moment I have no means of ascertaining, is threatened with violation and there is no way by which I can save her, then it would be the purest form of ahimsā on my part to put an end of her life and surrender myself to the fury of the incensed ruffian.

He is saying here that if a "ruffian" were to threaten his daughter with rape, Gandhi would murder her --- not him but her --- and offer his own body in her place.

I had to read this one over several times, thinking all the while that this seems a bit of what Esquire magazine used to call "wretched excess." He possibly reframes it at the end of the same passage: "A votary of ahimsā would on bent knees implore his enemy to put him to death rather than humiliate him or make him do things unbecoming the dignity of a human being." Still, the message is that he loves chastity more than he does his daughter.

There are other seeming contradictions in Gandhi's teaching. When World War I began, he urged his followers to take up arms for England. In his Autobiography he wrote, "I thought that England's needs would not be turned into our opportunity [to demand the end of English rule over India], and that it was more becoming and far-sighted not to press our demands while the war lasted. I therefore adhered to my advice and invited those who would enlist as volunteers."

In this Gandhi was consistent --- not with his acceptance of violence --- but rather, in his acceptance of England. He certainly knew early on that his controversial means of getting his way would only work within a democratic framework. If he had tried passive resistance --- sit-ins, fasting, non-violent demonstrations --- with any other political system, he would not only lose, he would lose his life.

Putting it more succinctly, passive resistance in the Germany of Kaiser Wilhelm (or worse, the Nazis), would have gotten him nothing but a death sentence. On the other hand, in England at the time of the raj, there was an odd democratic honor, even in the colonies, that would get him jailed without threatening his life. And when, in Gujarat in 1922, Gandhi invoked satyāgraha (nonviolent resistance, strikes, fasting, non-coöperation), he was arrested and sentenced to six years in prison, which worked well for him. This time gave him the chance to write endless articles and books, to practice his craft, to further teach himself the art of literary as well as political persuasion.

§ § § On the subject of chastity --- or as he would have it --- purity, Gandhi comes close to taking up the banner for the Catholic church. He states plainly that a couple should "never have sexual union for the fulfillment of their lust, but only when they desire issue ... the world depends for its existence on the act of generation, and as the world is the playground of God and reflection of His glory, the act of generation should be controlled for the ordered growth of the world."

Thus the pleasures of the flesh that most of us take for granted were, to Gandhi, an encumbrance. His pleasure, he reveals, is one of ridding himself of all possessions. "And, as I am describing my experiences, I can say a great burden fell off my shoulders, and I felt that I could now walk with ease and do my work also in the service of my fellow men with great comfort and still greater joy. The possession of anything then become a troublesome thing and a burden."

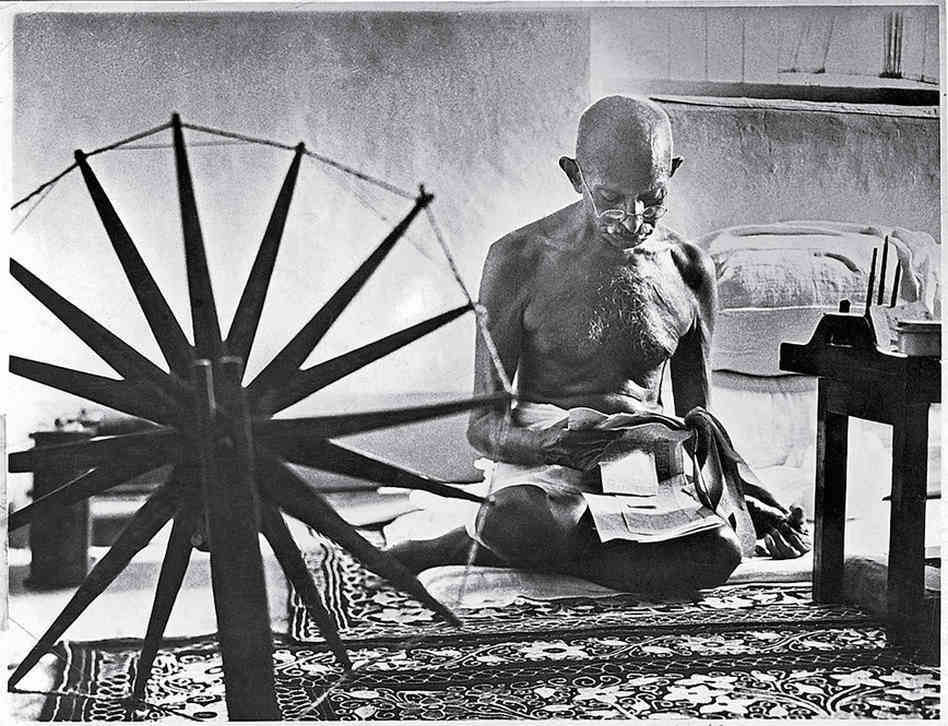

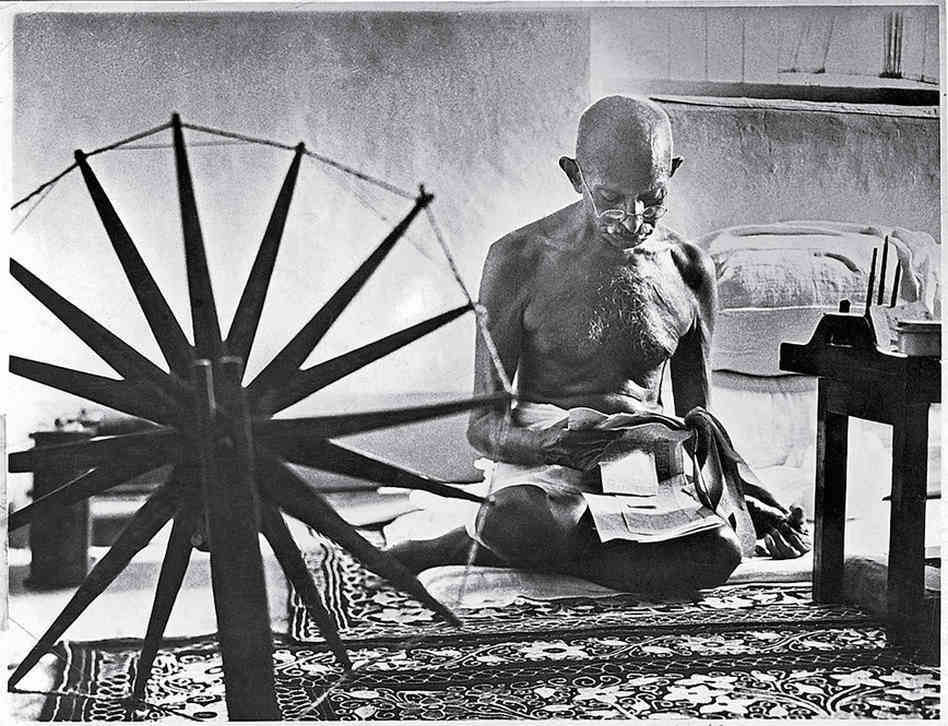

The spinning wheel was a familiar symbol to the followers of Gandhi. He revered the simplicity of it, the challenge of men taking up something that in those days would be seen as only part of the universe of women. He had chosen it as a way the poor of India could bring in a minimal amount, anything to keep them from starving to death.

The spinning wheel became an alternative to the machinery of the new capitalism, and --- in the face of it --- Gandhi showed himself to be a Luddite. "I don't believe that industrialization is necessary in any case for any country," he wrote to one of his correspondents.

Indeed I believe that independent India can only discharge her duty towards a groaning world by adopting a simple but ennobled life by developing her thousands of cottages and living at peace with the world. High thinking is inconsistent with a complicated material life, based on high speed imposed on us by Mammon worship.

"All the graces of life are possible, only when we learn the art of living nobly," he concludes. His specific complaint was against the so-called "labor-saving machine."

Men go on 'saving labor' till thousands are without work and thrown on the open streets to die of starvation.

His solution was to make the spinning wheel the center of Indian home life; a simple, labor intensive machine that could be built and operated by any and all, earning just enough to give a poor family what it might need to survive. "I have not contemplated, much less advised, the abandonment of a single healthy, life-giving industrial activity for the sake of hand-spinning," he wrote in his newspaper, Young India.

The entire foundation of the spinning wheel rests on the fact that there are crones [ten million] semi-employed people in India.

It was the answer to the "enforced idleness for nearly six months in the year of an overwhelming majority of India's population, owing to lack of a suitable supplementary occupation to agriculture and the chronic starvation of the masses that results therefrom."

He saw it as an astonishingly simple solution for the eternal problem of poverty that curses the indigent of all nations. It offered a craft that could produce something tangible (the spinning of cotton cloth, to be made into clothing, something to use or to sell) --- a simple instrument that would begin build a new but honored mini-industry, one that would take the edge of hopelessness from those who seek but to give sustenance to their families.

Could there be something this simple, this pure that could lift contemporary American inner cities out of their eternal cycle of beggary; something so elementary to displace the misery that plagues the poor, inflames the underemployed, haunts the souls of our once great cities?

A cynic might say that Americans have already found the appropriate diversions for the have-nots: sex, drugs, gambling, firearms, religion and the last offices of the deceased. These six commodities rule the neighborhoods of the very poor, appear to be the only route to sustenance left for those who want to survive, the only means to replace the millions of jobs that have been shipped off to China, Indonesia, Central and South America and --- yes --- India.

Is there nothing as appealing as Gandhi's simple spinning wheel, a device that could be quickly introduced into the universe of the destitute --- a magic touchstone that could offer a hope for the needy, an opportunity for the penniless, a dream for the impoverished --- a simple machine that would give dignity and even a small pittance to those who have but nothing left in this world.

--- L. W. Milam