Refugee Hotel

Gabriele Stabile

Juliet Linderman

(Voice of Witness /

McSweeney's Books)

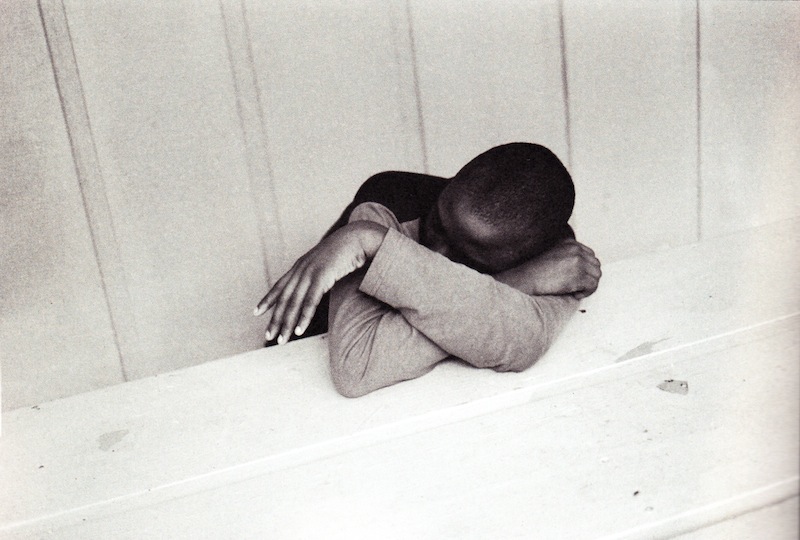

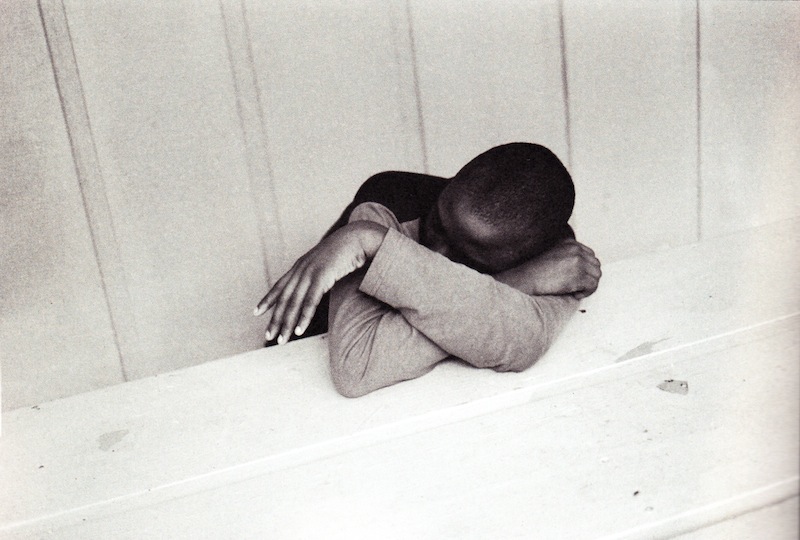

Several years ago, photographer Gabriele Stabile began collecting shots of the overnight tenents of "refugee hotels." These are way-stations located adjacent to refugee entry points in the United States. In these rather seedy hotels, newcomers are given rooms for their first night in this country. All are located next to the five big ports of entry for refugees under the International Organization for Migration program: New York, Newark, Chicago, Miami, and Los Angeles. (Between 2001 and 2010, IOM managed the resettlement of 810,000 refugees fleeing wars and military dictatorships in Bhutan, Iraq, Sudán, Burma, Burundi, Ethiopia, and Somalia.)Stabile roamed the halls of these hotels, collecting thousands of photographs of people both in transit and, later, in their final homes in such places as Amarillo, Mobile, Fargo, Erie, Minneapolis, and Charlottesville, Virginia. She and Juliet Linderman went to these cities to collect memories of those she had met and recorded before. Their stories are included here, in the center-section, some brief, some longer ... almost all narratives of woe: seeing a brother or a sister or a member of the family shot dead, buried in rubble, lost crossing a river or a border.

"To be called a refugee is bad," says one of the newcomers. "It means I have no country, no home, and that I'll always be running away." Another arrival, from Bhutan, travelled from Gelephu to Nepal to New Delhi to New York, Chicago, and ended up in Fargo. He had never seen snow before he arrived in North Dakota. He said, "When we went outside, we through someone had thrown salt on the ground, but when we tried to grab it, it was freezing cold."

Some people in the [refugee] camp told us that there are no trees in the U. S. --- that it's only in cities, and the people there don't leave their homes. But in North Dakota, we saw trees and land. I was relieved, I was happy.

We learn of insights from the volunteers from IOM as well. One resettlement worker in Charlottesville, Virginia tells of easily finding a job for a former tiger hunter from Burma, but that "It is more difficult with doctors and lawyers; they're never emotionally and mentally prepared for the reality of not being able to practice here right away."

This volume is compact and elegantly put together. There are over sixty color plates, more than seventy in black-and-white. Some --- especially the color shots --- are distant, out-of-focus, look like what you and I might see out of the windows and doors of a nondescript airport hotel. The others, mostly b&w, show us the final location, in Texas or Minnesota or North Dakota: children playing on the streets, a religious service, a boy with a guitar, another with a primitive computer.

The stories told by the photographs make fine counterpoint to narratives of the woes of leaving home for refugee camps, the bewilderment of arrival in this country, the hard job of resettlement. Osman Mohamed from Somalia says that when he is asked, he always claims to be from Kenya or Mozambique. "I'm not Somali." Why? "Somalia has nothing to show for all the killing." He has thus lost the land of his birth. But there is a new world for him and his family in Pennsylvania.

Now Erie is my home. I made that decision: this will be our house, our home, we're not going to move anymore, ever again. We will live and die in Erie, and be happy.

--- Richard Saturday