The Red Star

Thayer is gradually refreshed by the night air, making him even more aware of an excitement that has begun to churn through his clotted being, radiating from Bint's touch. The time in the tea room, with its talk of troops and dervishes, evaporates as quickly as a desert puddle. Although he's aware that their closeness has already come up against the borders of propriety, he doesn't pull away.The stars are out, as they've been every night for the past two years and in the hushed ages before them, dependably in their places as the seasons rotated through the crystal empyrean. Now it's the month of April, well into the night. The Great Bear has begun to lumber beneath the horizon, making way for the Virgin and the lush lactic wash of the Milky Way The planets tumble through their epicycles. The moon has already set. That makes it just past three. The seeing is excellent, eight or nine of ten on the Douglass Scale, marred only by some shifting currents in the upper atmosphere. Nights like these always intoxicate him with their possibility. Half the universe hangs above the desert floor, each star its own sun, each sun circled by worlds composed of the same elements that animate matter on Earth. The sky may be as alive as a deep warm pond in a sunny glade.

In the east the luminous star in Aquila draws his attention. He lifts his arm to it.

"That is Alpha Aquilae," he says. "Otherwise known as Altair." He's surprised when this prorvokes an open smile, as strong an expression of Bint's sentiments as he's ever witnessed. As she puts his things in order or brings him his meals, her gestures are more likely to be demure and self-contained. She tends to hover into visibility and then, before he can establish her presence, she vanishes. Now she repeats the star's name, casting it with a foreign inflection, "Al-toir."

"That's originally Arabic," Thayer concedes. "Altair, 'the flying eagle.' Or vulture."

"Al-nasr al-tair," she declares. This is the star's full appellation, in Arabic. She raises her arm abruptly and points not far from Altair, to an even brighter star. "Wega," she says.

Bint speaks so rarely that the sound of her voice is like the disclosure of a secret. The syllables emerge softly and resonant. He gazes with her at the second star, white with a touch of sapphire, so radiant they can almost be warmed by it.

"Vega," he confirms. "So you know some of the sky."

She extends a long finger with clipped, unvarnished nails at another blue-white first-magnitude star, about twenty degrees from Vega. It's the most prominent object in Cygnus and also commands an ancient name that has survived intact its passage through the Greek and Latin cosmologies. "Deneb," she says.

How many Arab girls in camp, or fellahin in the work crews dozing tonight alongside their excavations, can identify the vertices of the conspicuous, nearly equilateral triangle, Altair-Vega-Deneb, that dominates the Northern Hemisphere's sky on spring mornings and summer evenings? For the most part they never look upward, their attention fixed on the immediate and the mundane, the terrestrial.

"That's right, Bint. Very good."

Grinning now, he shows her the pale yellow light in the south-west, burning steadily close to Spica. This is a trick. It's not a fixed star.

Thayer says, "Saturn. The planet Saturn."

Bint repeats, "Saturn." She hesitates for several moments before she adds, "Zuhal."

He's astounded. "Zuhal?" He didn't know the Arabic name for the planet.

She smiles back, shyly. His sudden attention is intimidating. Thayer rarely has occasion to look at the girl directly. "Zuhal," she asserts.

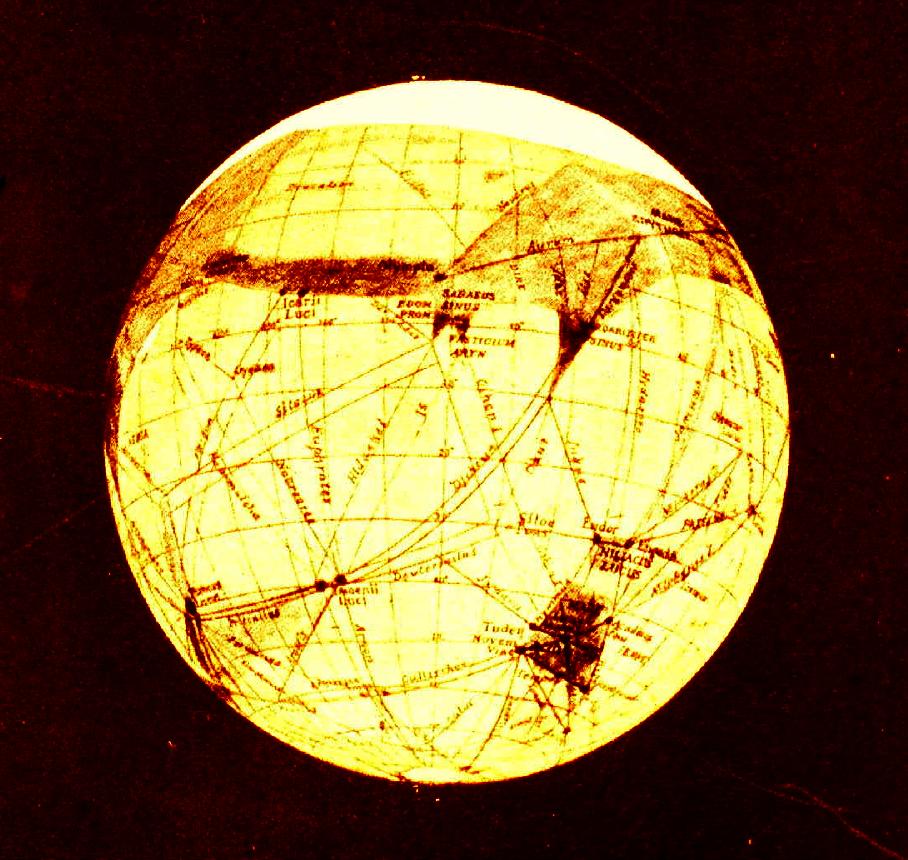

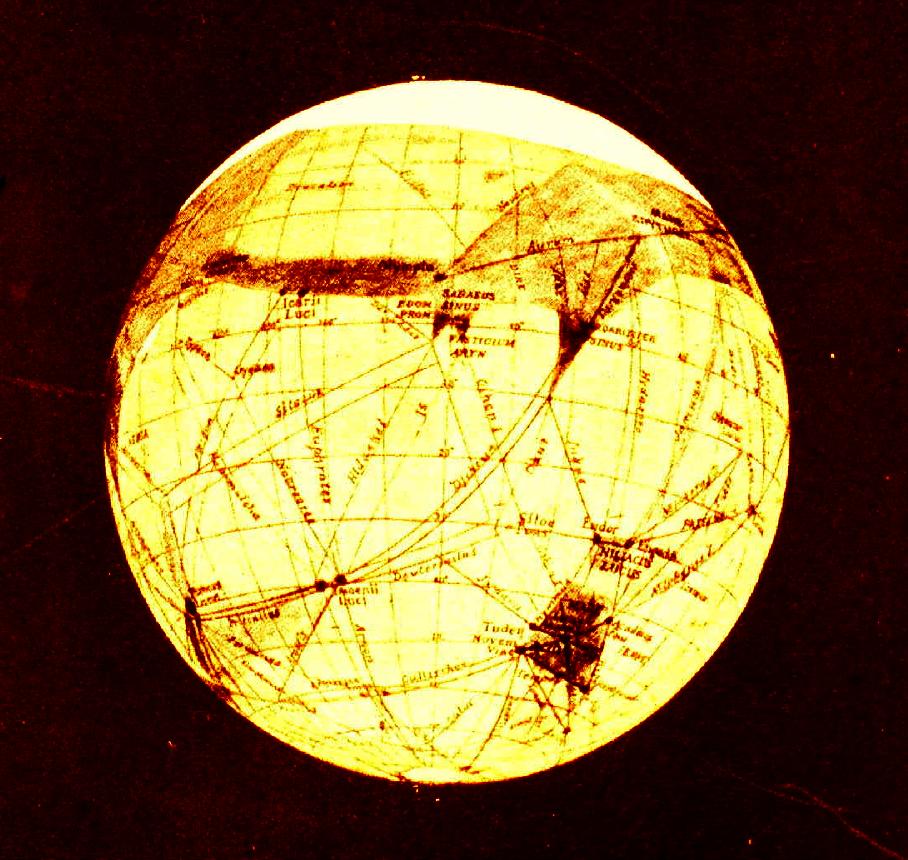

Saturn: one of the torrid giants like Jupiter, still solidifying into planetary form, a vast seething cauldron of vapors, impossibly hostile to life. But as the spheres cool over the next hundreds of thousands or millions of years, according to the principles of planetary evolution as laid out by Kant and Laplace, and then developed by Chamberlain and refined by Thayer, each sufficiently large planet will get its turn. The evolution of worlds is no less inevitable than the evolution of the species inhabited by them, followed by the evolution of those species' intelligences.

Thayer and Bint continue several yards toward his compound and then stop. He turns due east and looks across the wastes to a point just above the Egyptian horizon, past the temples at Luxor and the Mohammedan's holiest places. The night has gone cold. Some fine grains are swirling up from the Sudan. He softly touches her arm.

They both see it rising, our most beguiling planetary neighbor, red like a pomegranate seed, red like a blood spot on an egg, red like a ladybug, red like a ruby or more specifically a red beryl, red like coral, red like an unripe cherry, red like a Hindu lady's bindi, red like the eye of a nocturnal predator, red like a fire on a distant shore, the subject of his every dream and his every scientific pursuit.

"Mars," he says.

"Merrikh," she tells him.

He repeats after her: "Merrikh."

He admires the sound of it, biblical and arid and altogether strange. Merrikh.

She says the word again, emphasizing the final voiceless velar fricative, so favored in the East.

"Merrikh," he says, indicating the planet again, and then he points to the ground. "Earth."

She says, "Masr." Masr is the Arabic word for Egypt. She pronounces it with a Bedouin drawl.

He corrects her gently. "Earth."

"Urrth, Masr. Masr; Urrth." She smiles again, believing that she's learned another word of English.

Perhaps if Thayer knew the Arabic name for our planet he would set her right. But he doesn't know it and the thought occurs to him that a separate word for Earth, analogous to other planetary names, presumes an awareness that Earth, Mars, and Saturn are analogous entities, similar spheres similarly hurtling through the same celestial environnent, an airless, matterless medium known as "space." It also presumes an awareness that other political and national entities have been established on Earth, apart from Egypt.

---From Equilateral

Ken Kalfus

©2013 Bloomsbury