Karl Bodmer's

America Revisited

Landscape Views Across Time

W. Raymond Wood,

Robert M Lindholm

(Oklahoma)

Karl Bodmer came to America in 1832 with his patron, Prince Maximilian. The two were probably among the first eco-tourists, and they practically spanned the whole country, going from Boston to St. Louis, from thence to Fort McKinzie (in what is now Montana), and from there back to Boston. Travel in the Wild West in the age of Jackson was, to say the least, wild. You could be charged by bats, bears, bison and Baptists --- the Second Great Awakening was sweeping the country and dementing the gentry. Diseases could sweep you away in a trice: yellow fever, smallpox, typhoid, malaria, cholera, and tuberculosis. Visitors from abroad noted the virulent drunkenness among the poltroons, and shoot-outs in the bars and on the streets was a favored form of entertainment.Travel in America in that time was indeed onerous. For those heading west, there were four forms of transportation: stage coach, horse, on foot, and boats: launches, keelboats, paddle-wheelers, or canoe. Boats would founder as they moved upriver. At times the Prince and Bodmer were on vessels that moved so slowly (the Missouri River was among the most frustrating) that the two explorers were able to go ashore and plod ahead of their keelboat, the Flora. The two brought aboard plant and animal specimens and stones, which the crew often threw out, since they were the ones who had to drag the vessel upstream against the current: "Collecting rocks agin, hunh, Prince?" they would sneer as they tossed them overboard. The first winter was spent in Ft. Clark in quarters that were hardly luxurious (leaky doors and windows, snow on the floor), and the Prince came down with scurvy.

There were also a few problems with the Indians: not only were the Sioux on the warpath against the Yankees, they were entangled in other complicated skirmishes with the Mandans, Crees and Assiniboins. It took Maximilian and Bodmer two years to reach Fort McKinzie, and the miracle of it was that they actually traveled 3,000 miles to this far western point and then were able to retrace their path back to Boston and on to Europe.

Prince Maximilian Alexander Philipp was from Wied-Neuwied (in what is now Germany), and he was a hardy old bastard, and obviously had good taste in art and artists. Johann Karl Bodner was from Switzerland, had been trained professionally, and the Prince simply hired him on for a decade or so to do his plants, animals, beesties, landscapes, and Indians.

Bodner's sketches are exact enough that the editors of this volume could and did spend several years travelling the same route to collect photographs of the same locations, using the original sketches, watercolors, and later paintings as a guide. Sixty-seven are included here.

We are thus able to compare a vista of the White Cliffs --- called "The Eye of the Needle" --- to the White Cliffs at Eagle Creek as they appear at sunset today. (The editors are careful to try to time the light and shadow to match the originals.) For instance, the weird prowlike rock formations --- called the "Grand Natural Wall" --- on the upper Missouri can be seen through Bodner's eyes, and then through those of the photographer. These twinned pictures shows not only Bodner's sense of color and contrast, but his ability to foreshorten the horizontal, to cast sheer rockface at the viewer. One thinks of Cezanne's similar ability to tilt his subjects --- a bowl of fruit, four card-players, the landscape of Provençe, even his wife --- so you fret that these objects are going to tumble right out of the frame and bonk you on the head.

There are some photographs here that can make those of us who love the natural and the wild want to grit our teeth or organize a march (or move to Provençe). There is a watercolor of a bend in the Missouri at the Blacksnake Hills, and it is a blessedly agrarian sketch, an elegant composition. It is set face-en-face with the same locale as it exists today which consists mostly of a ghastly series of big, vile cement pilings of the Interstate 29 business loop outside of St. Joseph, Missouri.

At Vincennes, Indiana, we see bucolic vistas from Warrior's Hill; today the same location shows us tract housing dumped here and there like the cat's breakfast, complete with telephone poles, overhead electric cables, and what looks to be a dusty gray 1987 Pontiac coupe with sunken tires and badly in need of a trip to the Qwickie Kar Wash there in St. Joseph.

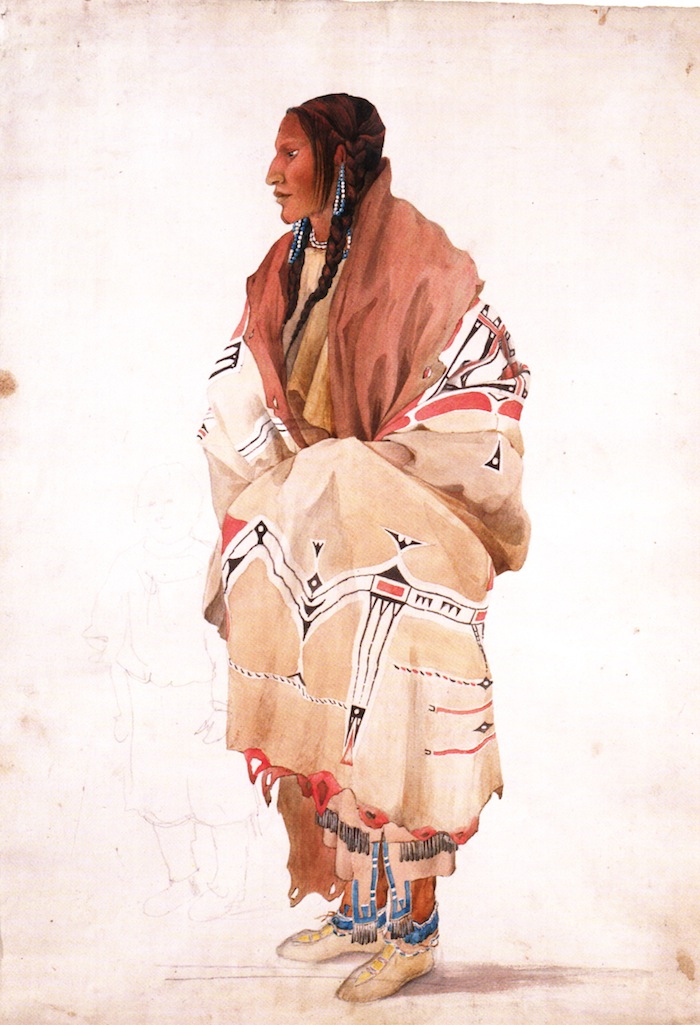

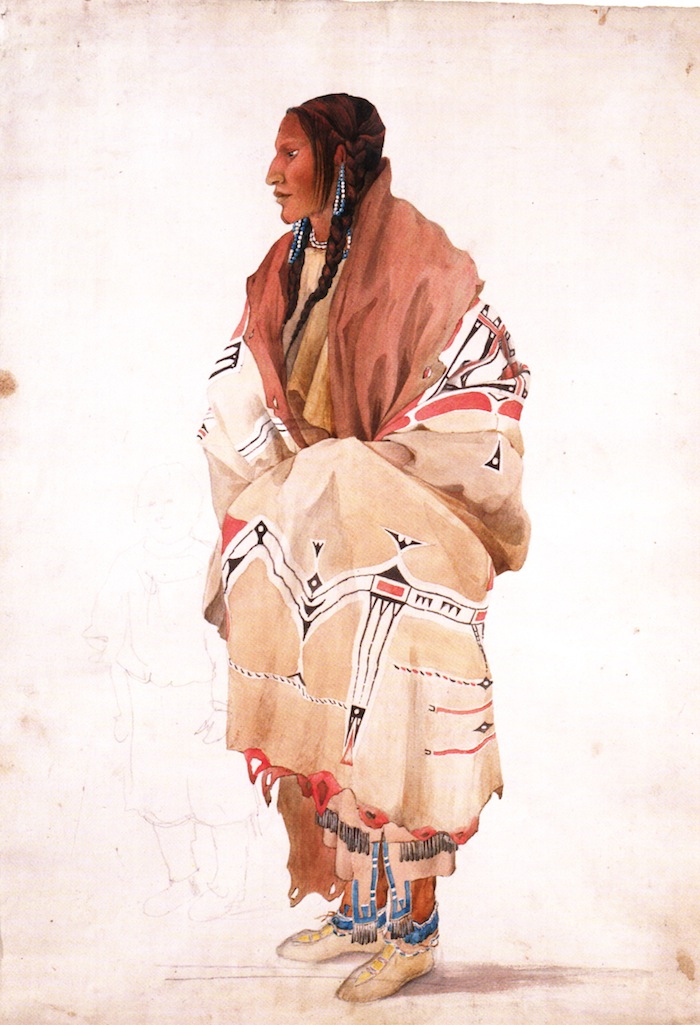

§ § § Many of the paintings here were composed after Bodner returned to Europe, and not a few of the watercolors and sketches he made as he travelled up and down the various rivers have been lost. The miracle is that what with all the rain, snow, dust, and being hauled down river, overland, and across oceans, some are as fresh and affecting as they were the day they were produced. Of especial interest to historians and those of us fond of the 19th Century are the the Indian paintings. The Chief of the Mandans Mató-Tópe, is shown in full headdress with body markings, as is the Chief of the Hidatsa, Addih Hiddisch. There are exacting drawings of feather headwear, and seven more of peace-pipes glorious enough to make you want to take up smoking again.

A drawing of Chan-Chä-Uia-Teüin [see Fig. 1 above] is so striking in composition and color and detail you want to call her up to find out where she got her magnificent handle. As is true of most artists, after the Prince died, Bodmer was left on his own in the garrets of Paris. "He was blind, nearly deaf, and reduced to poverty," the editors tell us. For those who want to know more about him and his works, they suggest the original Karl Bodmer's America, by William J. Orr, published in 1984 by by the University of Nebraska Press. Because of the present volume's classic style --- spacious and luxurious --- I highly recommend it to you. Karl Bodmer's America Revisited, comes from the University of Oklahoma Press. Praise them.

--- Richard Saturday